5 Surprising Facts About Skink Lizards You Never Knew!

Ever wondered about the secret world of skink lizards? Uncover 5 astonishing facts that will change how you see these reptiles. Get savvy with a read! Discover now.

Introduction

Slinking through leaf litter, basking on warm rocks, or darting between cracks in the earth – skink lizards are masters of adaptation and stealth. These fascinating reptiles belong to the family Scincidae, one of the most diverse lizard families with over 1,500 species worldwide. Despite their ubiquity across multiple continents, skink lizards often go unnoticed, overshadowed by their more flamboyant reptilian cousins.

Understanding skink lizards isn’t just an exercise in satisfying curiosity; it’s crucial for ecological awareness and conservation efforts. These creatures play vital roles in controlling insect populations and serve as important prey items in numerous food webs. As climate change and habitat destruction continue to threaten biodiversity, knowledge about these adaptable reptiles becomes increasingly valuable.

Did you know that some skink lizards can detach their tails when threatened and then grow them back? While tail autotomy isn’t unique to skinks, what’s particularly intriguing is that some species can actually distract predators by having their severed tail continue to wiggle and twitch for up to 30 minutes after detachment! This remarkable survival mechanism is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to skink lizard adaptations.

Species Overview

Scientific Classification

Skink lizards belong to the family Scincidae within the order Squamata, which includes all lizards and snakes. With about 150 genera containing more than 1,500 species, the skink family is one of the most diverse reptile families on Earth. Notable genera include Eumeces (North American skinks), Plestiodon (formerly part of Eumeces), Tiliqua (blue-tongued skinks), and Scincella (ground skinks).

Physical Characteristics

Skink lizards display remarkable physical diversity, but they share several distinctive features. Most possess cylindrical bodies with relatively short limbs and long tails, though some species have reduced limbs or are limbless altogether. Their most defining characteristic is their smooth, shiny scales that give them a sleek, polished appearance – almost as if they’re wearing armor.

The size of skink lizards varies dramatically across species. The smallest skinks barely reach 4 inches (10 cm) in total length, while giants like the Solomon Islands skink can grow up to 28 inches (72 cm) long. Color patterns range from plain brown or olive to brilliant blues, yellows, and reds, often with intricate patterns of stripes or spots that provide camouflage in their natural habitats.

Most skinks possess a distinctive transparent lower eyelid that allows them to see even with their eyes closed—a useful adaptation for burrowing species that need to protect their eyes from soil and debris.

Subspecies and Variations

Regional variations within skink lizard species are common, leading to numerous recognized subspecies. For example, the Western skink (Plestiodon skiltonianus) comprises three subspecies with slightly different appearances and ranges. The Common blue-tongued skink (Tiliqua scincoides) includes three recognized subspecies found across Australia and New Guinea, each with subtle variations in coloration and pattern.

Geographic isolation has led to remarkable evolutionary divergence, with island populations often developing unique characteristics. The genus Cryptoblepharus (snake-eyed skinks) demonstrates spectacular adaptive radiation across the Pacific and Indian Ocean islands, with distinct species evolving on different island groups.

Habitat and Distribution

Natural Habitat

Skink lizards have conquered an impressive range of ecosystems worldwide. These versatile reptiles thrive in environments ranging from tropical rainforests and temperate woodlands to harsh deserts and coastal dunes. Many species are ground-dwelling, hiding under rocks, logs, and leaf litter, while others have adapted to arboreal lifestyles in trees or bushes.

The substrate preferences of skink lizards often reflect their evolutionary adaptations. Burrowing species prefer loose, sandy soils where they can easily dig, while rock-dwelling skinks have evolved flattened bodies to squeeze into narrow crevices. Some specialized forest skinks live almost exclusively in leaf litter, navigating through the debris with snake-like movements.

Water requirements vary significantly among species. Desert-adapted skinks have evolved highly efficient water conservation mechanisms, while tropical species may require consistently humid environments to thrive.

Geographic Range

The global distribution of skink lizards is remarkable, spanning all continents except Antarctica. They reach their highest diversity in Australia, which hosts approximately 45% of all skink species—making them the most abundant reptile group on the continent. Other biodiversity hotspots for skinks include Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Pacific Islands.

North American skink species include the familiar Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus), while Europe hosts fewer species, with the European skink (Ablepharus kitaibelii) being the most widespread. South American skinks include various Mabuya species, and Africa boasts a rich diversity including the striking Fire Skink (Lepidothyris fernandi).

Island endemism is particularly common among skink lizards. Many island groups host unique skink species found nowhere else, making these populations especially vulnerable to extinction from introduced predators or habitat destruction.

Adaptations

Skink lizards showcase remarkable adaptations that have enabled their success across numerous habitats. Their smooth, overlapping scales reduce friction during burrowing and provide protection from abrasion. Many species have evolved elongated bodies with reduced limbs—an adaptation that facilitates movement through dense vegetation or narrow spaces.

Thermoregulatory adaptations are especially impressive, with different species evolving strategies for both hot and cold environments. Desert skinks often exhibit lighter coloration to reflect heat and may emerge only during cooler morning hours. Some cold-climate species, like the Northern Blue-tongued Skink, have developed viviparity (live birth) rather than egg-laying, allowing females to thermoregulate their developing embryos by basking.

Perhaps most fascinating are the anti-predator adaptations found in various skink lizards. Beyond tail autotomy (the ability to drop and regenerate their tails), some species have developed bright blue or red tails that serve as distraction displays to draw predator attacks away from vital body parts.

Diet and Feeding Habits

What Skink Lizards Eat

Skink lizards display impressive dietary diversity, with most species being omnivorous to some degree. Insects form the backbone of many skink diets, with beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, and caterpillars being particular favorites. Larger skink species may consume vertebrate prey, including smaller lizards, nestling birds, and even small mammals.

Plant matter is surprisingly important in many skink diets. Blue-tongued skinks, for example, consume significant amounts of fruits, berries, and flowers. Some species have specialized dietary preferences—Tiliqua rugosa (the Shingleback skink) is known to feed heavily on snails, using its powerful jaws to crush their shells.

Dietary shifts commonly occur throughout life stages, with juvenile skinks often focusing on protein-rich invertebrates to fuel growth, while adults may incorporate more plant matter. Seasonal variation in diet is also common, with many species taking advantage of temporary abundance of particular food items like seasonal fruits or insect blooms.

Hunting and Foraging Behavior

Skink lizards employ various foraging strategies depending on species and habitat. Most are active foragers, constantly moving through their environment using their acute sense of smell to locate prey. Their flickering tongue collects scent particles and transfers them to the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of their mouth, allowing them to “taste” the air for prey.

Visual hunting is also important, particularly for species that pursue fast-moving prey. Many skinks have excellent vision and can detect tiny movements from considerable distances. Some species, like the Blue-tongued skink, combine active foraging with ambush tactics, waiting motionless before launching surprisingly quick attacks on passing prey.

Feeding times typically correlate with thermoregulatory needs. Most skink species are diurnal (day-active), hunting during morning and late afternoon when temperatures are optimal for their metabolism. A few species have evolved nocturnal habits, especially in hot desert environments where daytime activity would risk overheating.

Dietary Needs and Adaptations

The digestive adaptations of skink lizards reflect their varied diets. Most species possess relatively simple teeth designed for gripping rather than chewing, though some specialized plant-eaters have developed more complex dentition. Blue-tongued skinks, for example, have strong, broad teeth suitable for crushing snails and plant material.

Metabolic adaptations include efficient energy storage systems that allow many species to survive lean periods. Desert-dwelling skinks can significantly reduce their metabolic rates during food scarcity, while some temperate species accumulate fat reserves before winter brumation (a reptilian form of hibernation).

Nutritional requirements vary between species but generally include proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Calcium is particularly crucial for proper bone development and egg production in females. Wild skinks obtain calcium from the exoskeletons of insects, small bones of vertebrate prey, or even by consuming calcium-rich soil in some cases.

Behavior and Social Structure

Social Behavior

The social structures of skink lizards span from strictly solitary lifestyles to surprisingly complex social groups. Most species tend toward solitary existence outside of breeding season, with individuals maintaining loose territories that may overlap. However, research has revealed unexpected social complexity in certain species.

The Australian Great Desert skink (Liopholis kintorei) exhibits a rare phenomenon among reptiles—family groups that include parents and multiple generations of offspring living in elaborate, shared burrow systems. These family units may persist for years, with parents actively protecting their young—behavior once thought impossible in reptiles.

Territoriality varies widely among skink species. Many maintain loosely defined home ranges rather than strictly defended territories. Males of some species become highly territorial during breeding season, engaging in combat with rivals through head-bobbing displays, posturing, and sometimes physical fighting. Blue-tongued skinks, for instance, may bite and grasp opponents in tests of strength.

Communication Methods

Skink lizards communicate through a sophisticated blend of visual, chemical, and tactile signals. Visual communication includes distinctive body postures, head bobbing, and tail displays. Some species change color during social interactions—males of certain skink species develop bright breeding colors to attract females and intimidate rivals.

Chemical communication is perhaps even more important for most skinks. They leave scent trails via specialized femoral pores and cloacal glands, creating chemical “messages” that convey information about species, sex, reproductive status, and individual identity. This chemical language allows skinks to communicate even when not physically present.

Tactile interactions are common during courtship and mating. Male skinks often grasp females gently with their jaws during courtship—a behavior that may seem aggressive to human observers but serves as an important part of the mating ritual. Social species engage in various forms of physical contact, including basking in close proximity to share warmth.

Mating and Reproduction

Reproductive strategies among skink lizards show remarkable diversity. Most species are oviparous (egg-laying), but approximately 45% of skink species are viviparous (live-bearing)—the highest percentage among lizard families. This evolutionary adaptation allows skinks to inhabit colder climates where egg incubation would be challenging.

Courtship typically involves elaborate male displays. Males may pursue females persistently, performing ritualized movements including head bobbing and circling. In some species, males may guard females from rival suitors for extended periods before and after mating.

Parental care, once thought rare in reptiles, is surprisingly common in certain skink species. Female skinks often guard their eggs, with some species coiling around egg clutches to protect them and regulate moisture and temperature. The Solomon Islands skink (Corucia zebrata) demonstrates extensive parental care, with females giving birth to one or two large, well-developed young that remain with their mother for months after birth.

Conservation Status

Endangerment Level

The conservation status of skink lizards varies dramatically across species. According to the IUCN Red List, while many skink species remain in the “Least Concern” category, approximately 18% of evaluated skink species face some level of threat. This includes species classified as Near Threatened, Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered.

Island endemic skinks face particularly dire situations. The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) is now extinct in the wild, surviving only through captive breeding programs. The Grand Skink (Oligosoma grande) of New Zealand is classified as Endangered, with severely fragmented populations continuing to decline.

Population trends for many skink species remain poorly understood due to their secretive habits and the challenges of conducting reptile surveys. This data deficiency itself represents a conservation challenge, as species may be declining unseen until problems become severe.

Primary Threats

Habitat destruction stands as the most pervasive threat to skink lizards worldwide. Agricultural expansion, urban development, mining, and forestry practices continue to fragment and destroy critical skink habitats. Many specialized skink species cannot survive in altered landscapes, particularly those with specific microhabitat requirements.

Invasive species pose catastrophic threats, especially to island skink populations that evolved without natural predators. Introduced cats, rats, mongoose, and even invasive ants have decimated numerous skink populations. The Mourning Skink (Emoia nigra) disappeared from Guam following the introduction of the Brown Tree Snake in the mid-20th century.

Climate change presents emerging challenges through altered rainfall patterns, increased temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events. Research suggests that climate change may particularly impact reptile sex determination in species where incubation temperature influences offspring sex ratios, potentially skewing populations toward one gender.

Conservation Efforts

Habitat protection initiatives represent the frontline of skink conservation. Protected areas that preserve intact ecosystems give skink populations their best chance for long-term survival. In Australia, the Western Swamp Skink benefits from reserve protection in Western Queensland, while New Zealand has established several predator-free sanctuaries that protect endemic skink species.

Captive breeding programs have become crucial lifelines for several critically endangered skink species. The Christmas Island blue-tailed skink and Lister’s gecko are maintained in captive breeding programs at Taronga Zoo and other institutions, with the goal of eventual reintroduction when threats can be mitigated in their native habitat.

Invasive species management, including predator-proof fencing, targeted predator control, and eradication programs on islands, has shown promise for skink conservation. New Zealand’s ambitious Predator Free 2050.

5 Interesting Facts About Skink Lizards

1. Self-Healing Superpowers

Skink lizards possess some of the most remarkable regenerative abilities among vertebrates. Beyond regrowing their tails—which in itself is impressive—some species can actually control blood loss after tail detachment through specialized sphincter muscles that quickly close off blood vessels. Even more surprisingly, when a skink’s tail regenerates, it doesn’t just grow back as simple cartilage like in many lizards. Instead, it develops a cartilaginous tube that partially replaces the lost vertebrae, surrounds a regenerated spinal cord, and supports new muscle growth.

The Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus) exemplifies this regenerative marvel. When threatened, it can detach its brilliantly blue tail, which continues to wriggle vigorously for up to 30 minutes, effectively distracting predators while the skink escapes. The new tail, though slightly different in appearance and lacking vertebrae, functions remarkably well for balance and locomotion.

2. Birth Diversity Champions

Skink lizards exhibit the greatest reproductive diversity of any reptile family, with species that lay eggs (oviparous), give birth to live young (viviparous), and even some that fall somewhere in between (ovoviviparous). What’s truly fascinating is that researchers have documented evolutionary transitions between these reproductive modes occurring multiple times within the skink family, making them invaluable for studying how live birth evolves.

The Australian Three-Toed Skink (Saiphos equalis) represents a remarkable “evolutionary snapshot” of this transition. Different populations of this single species show different reproductive modes depending on their altitude—coastal populations lay eggs, while highland populations give birth to live young! This makes them one of the few vertebrate species caught in the evolutionary act of transitioning from egg-laying to live birth.

3. Maternal Dedication Beyond Expectation

Unlike the “lay-and-leave” approach of many reptiles, numerous skink species demonstrate extraordinary maternal care. The Solomon Islands Skink (Corucia zebrata) shows dedication worthy of mammalian mothers—females carry their developing embryos for 6-8 months, give birth to just 1-2 large offspring, and then protect and nurture these young for months afterward. These baby skinks even “nurse” from specialized patches on their mother’s body, licking nutritious secretions—a behavior once thought exclusive to mammals!

Even more surprising is the maternal sacrifice observed in certain viviparous skinks. The Southern Grass Skink (Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii) transfers nutrients directly to embryos through a primitive placenta. Research has shown that pregnant females continue supplying nutrients to developing offspring even when food becomes scarce, sacrificing their own body condition to ensure offspring survival—a level of maternal investment previously thought impossible in reptiles.

4. Masters of Disguise and Deception

Beyond their well-known tail autotomy, skink lizards employ sophisticated mimicry and deception strategies. Several species, including the Broad-headed Skink (Plestiodon laticeps), have evolved to mimic venomous coral snakes. When threatened, these skinks will hide their legs against their bodies, move with serpentine motions, and even flatten their heads to appear more snake-like.

Perhaps the most elaborate deception occurs in the Red-sided Skink (Trachylepis perrotetii) of Africa. Juveniles of this species have evolved to look strikingly similar to toxic centipedes, complete with bright red tails they wave like centipede antennae and movement patterns that mimic centipede locomotion. This sophisticated mimicry deters predators that have learned to avoid the unpalatable arthropods. As the skinks mature and grow too large for this disguise to be effective, they transition to more typical cryptic coloration—essentially changing their entire defensive strategy as they age!

5. Unexpected Sensory Superpowers

Skink lizards possess sensory capabilities that border on the supernatural. The Blue-tongued Skink (Tiliqua scincoides) can detect ultraviolet light invisible to human eyes, allowing them to see patterns on flowers and even on other skinks that we cannot perceive. These UV-reflective patterns may play important roles in species recognition and mate selection.

Even more remarkably, research has revealed that some skink species can detect Earth’s magnetic field and use it for navigation—a sense called magnetoreception. The Eastern Water Skink (Eulamprus quoyii) has demonstrated this ability in laboratory experiments, suggesting these lizards maintain an internal “compass” that helps them navigate back to home territories when displaced. Scientists believe specialized cells containing magnetic crystals (likely magnetite) in the skinks’ brains allow for this extraordinary sensory perception, similar to systems found in migratory birds and sea turtles.

Tips for Caring for Skink Lizards

Habitat Requirements

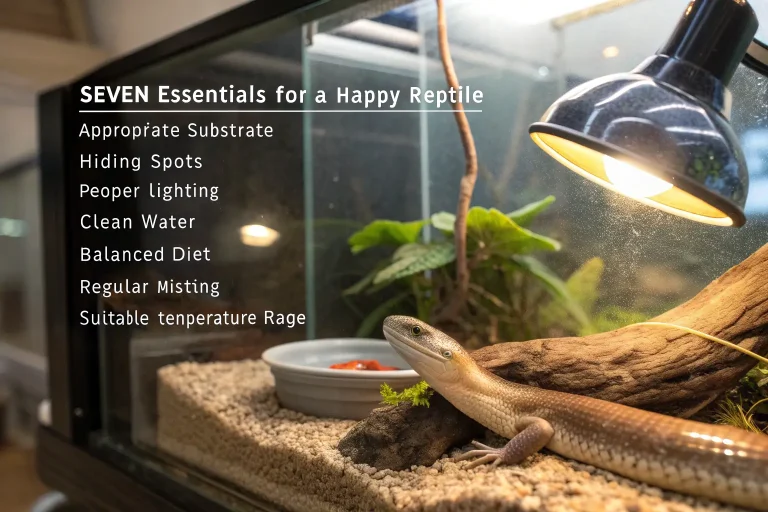

Creating a proper enclosure is crucial for keeping skink lizards healthy in captivity. The terrarium size depends on the species—smaller skinks like the Common Five-lined Skink require at least a 20-gallon terrarium, while larger species like Blue-tongued Skinks need minimum 40-gallon enclosures with floor space prioritized over height. Secure lids are essential, as many skinks are skilled escape artists.

Substrate choices should reflect the natural habitat of your particular skink species. Burrowing species thrive with a substrate mix of clean topsoil, play sand, and coconut fiber (at least 4 inches deep to allow natural digging behavior). Forest species do well with cypress mulch or orchid bark that maintains humidity, while those from drier regions prefer sand-soil mixtures.

Temperature gradients are vital—provide a basking spot of 90-95°F (32-35°C) at one end of the enclosure using appropriate heat lamps, with ambient temperatures decreasing to 75-80°F (24-27°C) at the cooler end. Nighttime temperatures can drop to 65-70°F (18-21°C). UVB lighting is essential for most skink species, as it allows proper calcium metabolism and prevents metabolic bone disease.

Diet and Nutrition

Feeding requirements vary substantially between skink species, but most captive skinks thrive on a varied diet. Insectivorous species require gut-loaded crickets, dubia roaches, mealworms, and superworms as staples. Omnivorous skinks like Blue-tongued Skinks should receive a mix of protein sources (insects, cooked eggs, lean ground turkey) and plant matter (dark leafy greens, squash, berries).

Proper supplementation is crucial—dust feeder insects with calcium powder (with D3) 2-3 times weekly for growing skinks and gravid females, and once weekly for adults. A high-quality multivitamin supplement should be provided once weekly. Always research the specific nutritional needs of your particular skink species, as requirements vary significantly.

Hydration needs also differ between species. Desert skinks may rarely drink from standing water, instead absorbing moisture from food and occasional misting. Tropical species require higher humidity and regular access to fresh water. Provide a shallow water dish that allows drinking but prevents drowning, particularly for smaller species.

Health Considerations

Common health issues in captive skinks include metabolic bone disease (from insufficient calcium or UVB), respiratory infections (from improper temperature or excessive humidity), and parasitic infections. Preventative care includes proper habitat setup, nutrition, and regular veterinary check-ups with an experienced reptile veterinarian.

Signs of a healthy skink include clear eyes, clean nostrils, proper shedding, alert behavior, and robust appetite. Watch for warning signs of illness such as lethargy, weight loss, abnormal droppings, difficulty shedding, or respiratory sounds. Quarantine new animals for at least 30 days before introducing them to established collections to prevent disease spread.

Proper handling techniques minimize stress. Support the skink’s entire body, never grab the tail (which could trigger dropping), and limit handling sessions to prevent overheating or cooling. Many skink species become quite tame with regular gentle handling, though temperaments vary significantly between species and individuals.

Role in the Ecosystem

Ecological Importance

Skink lizards function as crucial mesopredators in many ecosystems, controlling insect populations while themselves serving as prey for larger predators. Their insectivorous tendencies make them valuable natural pest controllers—a single garden skink can consume thousands of insects annually, including many agricultural and garden pests.

In some ecosystems, particularly island environments, skinks serve as important seed dispersers. Fruit-eating species like many blue-tongued skinks consume fruits and berries, then deposit seeds in their droppings across their territory, often in locations favorable for germination. Research in New Zealand has shown that native skinks play crucial roles in dispersing the seeds of several native plant species.

Soil health benefits from the burrowing activities of many skink species. Their tunneling aerates soil, allows water penetration, and redistributes nutrients throughout soil layers. Their droppings also contribute to soil fertility, completing nutrient cycling within ecosystems.

Impact of Decline

The disappearance of skink lizards can trigger cascading effects throughout food webs. When skink populations decline, insect prey may experience population booms, potentially leading to agricultural damage, plant defoliation, or disease transmission increases if the insects are vectors. Meanwhile, predators that rely heavily on skinks may face food shortages.

Trophic disruptions are particularly severe in island ecosystems with limited species. In New Zealand, where skinks were once extraordinarily abundant, their decline has impacted both the plants they helped propagate through seed dispersal and the specialized predators that evolved to feed on them.

Biodiversity losses extend beyond the skinks themselves. Many skinks host specialized parasites and microorganisms that co-evolved with them over millions of years. When a skink species disappears, these dependent organisms may also face extinction—representing an additional, often uncounted, biodiversity loss.

Conclusion

From their remarkable regenerative abilities to their unexpected maternal behaviors, skink lizards continually challenge our preconceptions about reptiles. These adaptable creatures have conquered diverse environments across the planet through evolutionary innovations that deserve both our scientific attention and conservation commitment.

The five surprising facts we’ve explored—their self-healing abilities, reproductive diversity, dedicated maternal care, sophisticated mimicry, and extraordinary sensory powers—only scratch the surface of what makes skink lizards fascinating. Each revelation invites us to reconsider our understanding of reptilian capabilities and intelligence.

As we face growing environmental challenges, protecting skink lizards and their habitats becomes increasingly urgent. Their ecological roles as insect controllers, seed dispersers, and vital links in food webs make them irreplaceable components of healthy ecosystems. By supporting conservation efforts, making sustainable choices, and sharing knowledge about these remarkable reptiles, we can help ensure that future generations will also have the opportunity to be surprised and delighted by the secret lives of skink lizards.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are skink lizards dangerous to humans or pets?

Most skink lizards are completely harmless to humans and pets. While larger species like Blue-tongued Skinks can deliver a painful bite if provoked, they’re typically docile and non-aggressive. Unlike some reptiles, skinks don’t produce venom or toxins. The most common North American species, like Five-lined Skinks, have mouths too small to effectively bite humans. If you find skinks in your garden, consider yourself lucky—they’re beneficial predators that help control pest insects naturally.

How can I tell if a lizard I’ve found is a skink?

Skink lizards typically have several distinguishing features: smooth, glossy scales that give them a polished appearance; a cylindrical body shape; relatively small limbs compared to other lizards; and a long, tapering tail. Many species have distinctive color patterns, like the Five-lined Skink’s blue tail and five light stripes running down its body (in juveniles). If the lizard moves with a snake-like undulating motion rather than the stop-start running of many other lizards, it’s likely a skink.

Why do some skinks have bright blue tails?

The vibrant blue tail seen in juveniles of several skink species (like the Five-lined and Broad-headed Skinks) serves as a predator distraction strategy. The bright color draws a predator’s attention away from the skink’s vital body parts and toward the expendable tail. When attacked, the skink can detach its tail (autotomy), which continues to wiggle vigorously, distracting the predator while the skink escapes. As these skinks mature, most gradually lose this bright coloration since adult skinks rely more on camouflage for protection.

Can I keep wild skinks as pets?

While it’s technically possible to keep wild-caught skinks, it’s generally not recommended for several reasons: wild skinks often carry parasite loads, may not adapt well to captivity, and removing them impacts local ecosystems. Additionally, in many regions, capturing wild reptiles requires specific permits. If you’re interested in keeping skinks as pets, purchase captive-bred specimens from reputable breeders. Captive-bred animals are typically healthier, more accustomed to human interaction, and their acquisition doesn’t impact wild populations.

Do skinks regrow their tails exactly the same if they lose them?

When a skink regrows its tail after autotomy (self-amputation), the regenerated tail differs from the original in several ways. The new tail lacks true vertebrae, instead forming around a cartilaginous tube. The scales on the regenerated portion often have a different pattern or coloration from the original tail, and the new tail may be shorter or slightly different in shape. In species with colorful juvenile tails, like the Five-lined Skink, a regenerated tail typically lacks the bright blue coloration of the original.